One of my enduring memories of my father’s illness is of his morning walk. Glancing out of my kitchen window, I would see him shuffling along with an attendant’s support, and my heart would contract. He had been a tea planter, walking ten miles effortlessly in the course of a day. To see him reduced to a doddering, inarticulate wreck decades in advance of his time was not something I ever got used to.

In another haunting memory, my son, then ten or eleven, newly enamoured of the daily newspaper, runs toward me excitedly waving a headline and shouting, “Look, Mumma! New cure for Parkinson’s!” I would sigh and hug him.

We had learnt long before that Parkinson’s does not have a miracle cure. It is a cruel, unpredictable disease that manifests in symptoms as unique to victims as their fingerprints. Tremor, rigidity, and slowness come in varying degrees, compounded by other symptoms.

My father endured long bouts of acupuncture, then Ayurveda, to no effect. ‘Stereotactic’ surgery gave him temporary parallel vision. One eye flopped over. A photograph of him with an eye patch at my cousin’s wedding serves as a permanent reminder to apply caution in the matter of proselytising doctors.

In 2001, I watched in silence as a colleague was seduced by one of those newspaper headlines. He borrowed Rs3 lakh for an operation to cure his father, determined that he wouldn’t suffer what his Parkinsonian uncle and aunt had: falls, broken bones, agonies while bedridden, and premature death. Tissue was implanted. In three months he succumbed to multiple infections and went from bed straight to crematorium. The headline hadn’t clarified that a patient on immunosuppressants would require a sterile environment.

But my dad was surrounded by knowledge and care. One of the first things he did was subscribe to the Parkinson’s Disease Society newsletter. While publishing research results cautiously, it offers advice on coping with dignity while adapting to the clumsy stranger gradually invading your body. His diet, medication, and physiotherapy was monitored by his most devoted attendant, my mother. She was no-nonsense Matron, setting impossibly high quality standards for the ones we hired. She made sure he ate all that we did – as he grew older and his teeth gave way, she would grind each delicacy separately. And my dad knew how to minimise damage when he fell, a poignant reminder of his days as a sportsman. So in twenty-six years, he broke only one bone.

When he lay in hospital, adapting to a synthetic-blended femur ball, my brother and I, our spouses and children, visited, gushing with affection and little treats, to which he responded well, being a man who was easy to please. Fifteen years into the disease, conversation was a chore. By the time he worked up a few words, the other person would have given up. We tried our best, but it was a protracted process.

He passed the time playing chess. To move a piece he’d recruit his opponent’s help, relaying instructions through cryptic signals of eye and head. One day, as a lovely young physiotherapist manipulated his limbs and led him through breathing exercises, another young woman in a white coat peered around the door, scolding: “That’s my patient!”

His face expressionless (another symptom of Parkinson’s), he mouthed, in hoarse, gravelly tones: “Turf wars!”

I guffawed aloud, delighted as much with the joke as with his still-vibrant sense of humour. They turned wary, uncomprehending eyes on me.

Sadly, the stretch in hospital was followed by bed sores, and took months to heal. My mother dusted antiseptic powder and made sure he was turned every half hour. We watched helplessly when he groaned in pain, and she alternated kind caresses with stern orders to behave.

Nursing help, a fledgling industry, presents ludicrous schisms between front-office sales and back-office service. Promising angels of mercy, the bureaus in my city dispatched louts off the street who slouched and scratched their bottoms. They arrived, if at all, long after the night-shift helper – an angel of mercy, a woman – had left. One man arrived just in time to help me through a toilet crisis. He shook his head, muttering repeatedly, “Oh my god, what a nuisance!” and luckily slipped away, without notice, before I slapped him. Even those with hospital experience would collect a tidy lumpsum after a few days and stay home to booze it up. Nilesh, gentle and proficient, lasted a good stretch until one day he tootled off on the mali’s bicycle and never came back. The bureaus are still calling, a year after I don’t need them any more.

My father had been diagnosed at fifty. He was seventy-six when he died last year. We sat with the body, reflecting. He had suffered so much in the last few months that I felt glazed with relief. Only later would I mourn the loss of someone who could feel my pain; whose quiet courage had given me the strength to face the challenges of my own life. There’s no tonic more motivating than a father’s pride, even when the silent glow is barely perceptible behind an impassive, Parkinsonian face. I said, “D’you think he’d have liked us to have an Irish wake?” “What’s that?” asked my daughter. “No idea,” I replied, “I think they stay up all night drinking and dancing.” “Oh,” she said, deadpan, “I thought that was called Friday night.”

It was his genius for spotting the comic heart of a situation that had taught us to take our troubles lightly. We turned to him, anticipating the characteristic half-smile, but he lay still and unresponsive. The current Economist, subscription a thoughtful gift from my brother, remained unopened.

When I was little, my father gave me stylish haircuts and the other plantation wives begged him to do the same for their daughters. “Can’t smack them if they fidget,” he explained, by way of polite refusal. My brother wept copiously when he told us about Oliver Twist, Sohrab and Rustom and others – while I reached for another cutlet, thinking, “Life is tough, get used to it, er, Portia.” He had a tuneful singing voice his grandchildren would never hear. We lived in the house on the hill, and he was lord of all we surveyed. Years later when I visited with my kids, enthusiastically pointing out my old carved rosewood cupboard and an iron stove just like the one we’d seen in the kitchen of Henry VIII’s Hampton Court, people remembered him as the one who rode through the fields with our dog balancing coolly on pillion.

If we ever saw a quivering, dribbling, old man my father would shudder and say, “Poor fellow! I hope I never get that way.” In later years we never pre-empted disease; never made flippant statements about health.

By saying, expansively, “You can be anything you want,” he gave me freedom of choice, appreciation of competence – and permission for situational nonconformity. At boarding school, I once received a letter containing something he’d liked and typed out, with a note saying I should read and pass it on to my brother: “Ten lessons for my sons”. I suppose it was this, compounded by my brother’s unremitting generosity, which had me performing his cremation rites.

As we grew older, and he became more disabled and dependent, he became our role model of dignity and gracious acceptance. We learnt from him that it was possible to be a responsible person and participate in the joy of living even within the narrowest parameters. As his ability to communicate reduced, we learnt that silent dignity carries its own message. Those around him, many who had never known him as we had, full of humour, kindness and vitality – even strangers – continued to respond to him with the same quality of affection and regard that he had always drawn.

My father left me with a room of my own: a position from which, as Virginia Woolf eloquently observed, one’s publishers’ political affiliations are of little consequence. Embroiled recently in a compromising hospital procedure, I drew courage from the memory of his stoic bravery when faced repeatedly with worse. It struck me that his real legacy was the comprehension that disability cannot prevent anyone from living life to the full, with good humour, wit, and dignity.

In another haunting memory, my son, then ten or eleven, newly enamoured of the daily newspaper, runs toward me excitedly waving a headline and shouting, “Look, Mumma! New cure for Parkinson’s!” I would sigh and hug him.

We had learnt long before that Parkinson’s does not have a miracle cure. It is a cruel, unpredictable disease that manifests in symptoms as unique to victims as their fingerprints. Tremor, rigidity, and slowness come in varying degrees, compounded by other symptoms.

My father endured long bouts of acupuncture, then Ayurveda, to no effect. ‘Stereotactic’ surgery gave him temporary parallel vision. One eye flopped over. A photograph of him with an eye patch at my cousin’s wedding serves as a permanent reminder to apply caution in the matter of proselytising doctors.

In 2001, I watched in silence as a colleague was seduced by one of those newspaper headlines. He borrowed Rs3 lakh for an operation to cure his father, determined that he wouldn’t suffer what his Parkinsonian uncle and aunt had: falls, broken bones, agonies while bedridden, and premature death. Tissue was implanted. In three months he succumbed to multiple infections and went from bed straight to crematorium. The headline hadn’t clarified that a patient on immunosuppressants would require a sterile environment.

But my dad was surrounded by knowledge and care. One of the first things he did was subscribe to the Parkinson’s Disease Society newsletter. While publishing research results cautiously, it offers advice on coping with dignity while adapting to the clumsy stranger gradually invading your body. His diet, medication, and physiotherapy was monitored by his most devoted attendant, my mother. She was no-nonsense Matron, setting impossibly high quality standards for the ones we hired. She made sure he ate all that we did – as he grew older and his teeth gave way, she would grind each delicacy separately. And my dad knew how to minimise damage when he fell, a poignant reminder of his days as a sportsman. So in twenty-six years, he broke only one bone.

When he lay in hospital, adapting to a synthetic-blended femur ball, my brother and I, our spouses and children, visited, gushing with affection and little treats, to which he responded well, being a man who was easy to please. Fifteen years into the disease, conversation was a chore. By the time he worked up a few words, the other person would have given up. We tried our best, but it was a protracted process.

He passed the time playing chess. To move a piece he’d recruit his opponent’s help, relaying instructions through cryptic signals of eye and head. One day, as a lovely young physiotherapist manipulated his limbs and led him through breathing exercises, another young woman in a white coat peered around the door, scolding: “That’s my patient!”

His face expressionless (another symptom of Parkinson’s), he mouthed, in hoarse, gravelly tones: “Turf wars!”

I guffawed aloud, delighted as much with the joke as with his still-vibrant sense of humour. They turned wary, uncomprehending eyes on me.

Sadly, the stretch in hospital was followed by bed sores, and took months to heal. My mother dusted antiseptic powder and made sure he was turned every half hour. We watched helplessly when he groaned in pain, and she alternated kind caresses with stern orders to behave.

Nursing help, a fledgling industry, presents ludicrous schisms between front-office sales and back-office service. Promising angels of mercy, the bureaus in my city dispatched louts off the street who slouched and scratched their bottoms. They arrived, if at all, long after the night-shift helper – an angel of mercy, a woman – had left. One man arrived just in time to help me through a toilet crisis. He shook his head, muttering repeatedly, “Oh my god, what a nuisance!” and luckily slipped away, without notice, before I slapped him. Even those with hospital experience would collect a tidy lumpsum after a few days and stay home to booze it up. Nilesh, gentle and proficient, lasted a good stretch until one day he tootled off on the mali’s bicycle and never came back. The bureaus are still calling, a year after I don’t need them any more.

My father had been diagnosed at fifty. He was seventy-six when he died last year. We sat with the body, reflecting. He had suffered so much in the last few months that I felt glazed with relief. Only later would I mourn the loss of someone who could feel my pain; whose quiet courage had given me the strength to face the challenges of my own life. There’s no tonic more motivating than a father’s pride, even when the silent glow is barely perceptible behind an impassive, Parkinsonian face. I said, “D’you think he’d have liked us to have an Irish wake?” “What’s that?” asked my daughter. “No idea,” I replied, “I think they stay up all night drinking and dancing.” “Oh,” she said, deadpan, “I thought that was called Friday night.”

It was his genius for spotting the comic heart of a situation that had taught us to take our troubles lightly. We turned to him, anticipating the characteristic half-smile, but he lay still and unresponsive. The current Economist, subscription a thoughtful gift from my brother, remained unopened.

When I was little, my father gave me stylish haircuts and the other plantation wives begged him to do the same for their daughters. “Can’t smack them if they fidget,” he explained, by way of polite refusal. My brother wept copiously when he told us about Oliver Twist, Sohrab and Rustom and others – while I reached for another cutlet, thinking, “Life is tough, get used to it, er, Portia.” He had a tuneful singing voice his grandchildren would never hear. We lived in the house on the hill, and he was lord of all we surveyed. Years later when I visited with my kids, enthusiastically pointing out my old carved rosewood cupboard and an iron stove just like the one we’d seen in the kitchen of Henry VIII’s Hampton Court, people remembered him as the one who rode through the fields with our dog balancing coolly on pillion.

If we ever saw a quivering, dribbling, old man my father would shudder and say, “Poor fellow! I hope I never get that way.” In later years we never pre-empted disease; never made flippant statements about health.

By saying, expansively, “You can be anything you want,” he gave me freedom of choice, appreciation of competence – and permission for situational nonconformity. At boarding school, I once received a letter containing something he’d liked and typed out, with a note saying I should read and pass it on to my brother: “Ten lessons for my sons”. I suppose it was this, compounded by my brother’s unremitting generosity, which had me performing his cremation rites.

As we grew older, and he became more disabled and dependent, he became our role model of dignity and gracious acceptance. We learnt from him that it was possible to be a responsible person and participate in the joy of living even within the narrowest parameters. As his ability to communicate reduced, we learnt that silent dignity carries its own message. Those around him, many who had never known him as we had, full of humour, kindness and vitality – even strangers – continued to respond to him with the same quality of affection and regard that he had always drawn.

My father left me with a room of my own: a position from which, as Virginia Woolf eloquently observed, one’s publishers’ political affiliations are of little consequence. Embroiled recently in a compromising hospital procedure, I drew courage from the memory of his stoic bravery when faced repeatedly with worse. It struck me that his real legacy was the comprehension that disability cannot prevent anyone from living life to the full, with good humour, wit, and dignity.

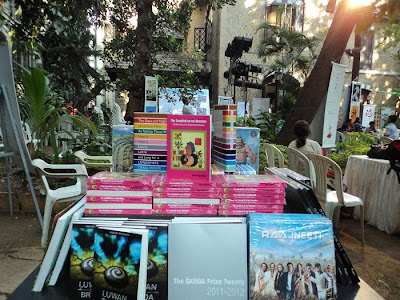

First appeared as ‘Living with Parkinson’s’ in Open magazine on 5 September 2011